Prequel Problems: The Duck Universe of Carl Barks and Don Rosa, Part I

- Feb 22, 2021

- 13 min read

By Max Lindh

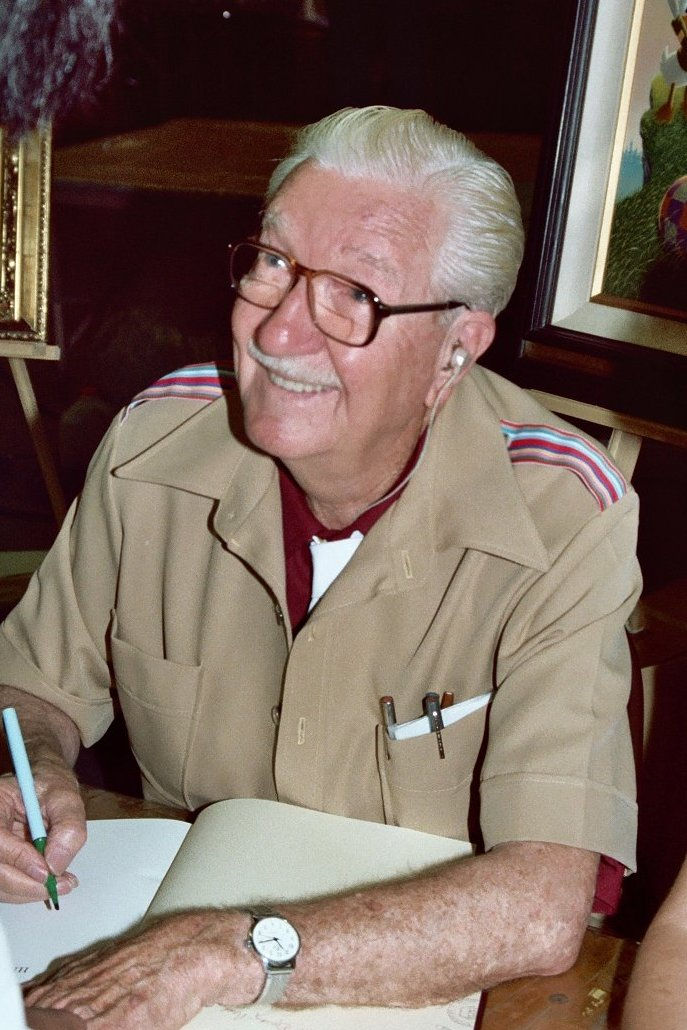

In Kentucky lives a former engineer by the name of Don Rosa, who in the 1980s decided to change gears and become a comic book artist. Although a fan of both Marvel and DC, Don Rosa felt that his calling was to the world of Donald Duck comics, and for that reason, his name remains rather obscure in the United States. Fond of musing as he is that his neighbours down the street on which he lives back home in Kentucky have no idea was he does—or rather, as he is now retired, did—for a living, the situation is quite different on the other side of the Atlantic, for in Continental Europe, where Donald Duck comics enjoy a far greater share of the market, his name carries just as much weight, if not in fact more, as that of Stan Lee. Though eye problems forced him to hang up his pen in 2006, still to this day when he makes his tours of Europe, he can count on being the headliner for comic book conventions, where he will be interviewed before crowded auditoriums, and where afterward, fans will stand in queue for ages to get his autograph.

Why do people love Don Rosa so much? Why, there can of course be no denial that his inimitable artistic style is one factor. Meticulous and highly detailed, they appeal to that same part of the brain as a Where’s Wally? puzzle, and Don Rosa’s Duck comics are known both for the extensive use of slapstick humour with background jokes, as well as very emotive facial expressions. Another factor is of course that he is keen to take his characters on wild escapades to far corners of the Earth (and beyond), involving exotic themes such Finnish mythology, Knights Templars, lost civilizations in the tropics, and French gentlemen-thieves. You know, the sort of stuff you would want from any good adventure story.

But, no! The real reason for Don Rosa’s popularity within the Duck comics community is because he is not just himself very much a fan of Duck comics—an inmate who has perhaps not come to run the asylum but who at the very least has connived his way into getting a permanent seat on its board of governors—he is also very keen on rewarding his readers for being fans themselves. His writing and his artistry is so full of references to other stories—sometimes in the form of simple blink-and-you’ll-miss-it details, sometimes central to the plot itself—that he may well be said to define the trope of Continuity Porn. Sometimes, often in fact, he goes further than that though, and the grand project of his career, of which his most celebrated work The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck merely forms the cap stone, can accurately be described as attempting to craft a single, internally consistent chronology and narrative for the universe of the Duck comics.

This is what makes Don Rosa, in my humble opinion, so incredibly awesome, and why he may rightly be counted as one of the greatest comic book artists in the past fifty years. It is also why his work is somewhat (and here I wish to stress that I am using the word in its traditional sense) problematic.

To explain why that is, we first need to go back to a time long before Don Rosa entered the stage, and explain how Donald Duck comics ever became a thing for which it even would make sense to discuss such notions as overarching continuity, and that story is the story of man by the name of Carl Barks.

Walt Disney had introduced Mickey Mouse to the world in 1928 with the animated short Steamboat Willie, with Goofy coming along four years later in 1932’s Mickey’s Revue, and finally, in 1934, Donald Duck made his debut in The Wise Little Hen. Within a few years, all three popular characters were appearing in comic strips in daily newspapers, and for Mickey Mouse, the character that Walt Disney put at the forefront of small but already expanding empire, there were even longer adventure stories being written. A famous example is The Mail Pilot from 1933, which sees Mickey Mouse as a flying ace in the service of the U. S. Post Office, fighting against a vast criminal empire headed by Peg-Leg Pete from a massive zeppelin in perpetual flight, hidden at the center of an artificial cloud generated by machines built by kidnapped chemists and engineers.

No, really.

It’s actually quite impressive for a comic book story from 1933.

Meanwhile, Donald Duck had to be content with the strips and one-pagers, grounded in a more quotidian setting, which arguably was where he was best suited. Anyone who has seen any of the old Silly Symphonies from the 1930s will know that Donald Duck is a very, shall we say, passionate character. He emotes, in particular when angry. Thus, it appealed to the writers and readers alike to envision Donald Duck as this chronically unlucky fellow who runs into comic mishaps and misunderstandings as he goes about his daily life in a suburban middle class setting. It was first in 1942 that the powers that be decided that Donald deserved a proper adventure of his own, and with sixty-four pages in colour, the story Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold was printed, which in as far as the basic plot is concerned is rather self-explanatory. Fittingly this is also where Carl Barks finally enters the scene.

Born in rural Oregon in 1901, Carl Barks had grown up in a time and a place where there were still a few pioneers from the old days hanging around. His family were never outright poor, but they always were of modest means, and living on a farm in a sparsely settled area, the young Carl never received much of an education. Leaving school in 1916, he would spend the next twenty years working a variety of odd jobs without much success, before finally, in the midst of the Great Depression, he decided to respond to a general call from the Disney corporation in 1935 asking for artists to apply for work. Drawing had long been a hobby of his, so judging by his lack of success in other employments and the general economic climate at the time, one can only assume that he must have felt fairly happy that he could now make it into a profession.

Though he started as a lowly animator, burdened with tedious task of drawing individual frame, he was within a few years contributing ideas and storylines for Silly Symphonies shorts. In 1942, he was one of the two artists who were tasked with providing the artwork for Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold, penned by Bob Karp, though it did not take long at all before Barks decided that it was far more satisfying to write the stories as well as to illustrate them. For the next quarter of a century, this was to be Carl Barks’ fulltime job, and in that period, through his work, he was to in essence create the Donald Duck comic universe as a living, breathing entity.

It is at this point that it becomes appropriate to discuss the framework within which Carl Barks and his fellow Disney comic writers and artists operated, and how much it differed from the millieu of their contemporaries elsewhere. Perhaps the most suitable person to compare Barks with is Georges Remi, better known as Hergé, the creator of Tintin.

From the very beginning, Tintin had been published under Hergé’s own name, and his various employers had been fairly relaxed about the amount of work that was expected from him, a mere two pages worth of comics a week which were published on a set date. (Later on, Tintin would get his own comic book, making Hergé his own boss, which allowed him even laxer working hours.) These weekly pages would be part of a serial, and as a general rule, it would take somewhat less than two years between Tintin heading off on a new adventure and him returning safe and sound to his home in Brussels. Once a serial had concluded, the weekly pages were gathered together and published in a neat album format with glossy cover. Consequently, if you were a French or Belgian boy or girl aged ten in 1959, you could still easily access and “binge” on Tintin’s adventures from the 1930s if you went to a book store or a library.

This format greatly encouraged longer story arcs, for instance, the two serials Cigars of the Pharaoh and The Blue Lotus—which form part of the same narrative—started serialization in December 1932 and first reached their epic conclusion in October 1935. It also encouraged great attention to continuity, and allowed Hergé to bring back into the story old characters who hadn’t appeared in Tintin for years (sometimes decades) without having to worry about potentially confusing his readers. And of course above all, since every time a boy or a girl decided to spend their allowance on a Tintin band dessinée, a share of Belgian francs and centimes would trickle ever so gently into Hergé’s personal bank account, which in particular encouraged Hergé to focus on quality over quantity.

Things were different in the United States, particularly if you were working for Disney. If you were working for them, you did not get paid in accordance with how well the weeklies with your stories or drawings sold, nor did you get paid royalties when reprints of your stories or drawings appeared. You got paid a set lump sum every time that Disney bought your work, and from that point on, it was entirely Disney’s intellectual property to do with as they pleased. To make matters worse for creators, company policy at the time dictated that all stories they publish be published anonymously, the only name that was allowed to be attached to them was that of Walt Disney. Further, the Disney company had yet to reach the conclusion that they could make money by publishing albums of reprints as was the fashion in France and Belgium, and so if you were a fan of Donald Duck comics aged ten in 1959, unless you had an older sibling or a friend who had been buying Duck comics at the time, or you were lucky enough to live in a place where you could buy old comics, it was going to be pretty difficult for you to get access to comics published even five years ago. And what with the aforementioned policy of mandatory authorial anonymity, how would you even know what to look for?

This environment had two big effects on the nature of the work Disney comic artists produced. First, it more or less forced writers and artists to constrain themselves to shorter, self-contained stories and adventures and made it impossible to establishing longer-running narratives. There was simply no incentive for greater continuity, nor disincentive for discontinuity, and certainly nobody could be expected to remember a Donald Duck story that had run three years or more earlier. Second, and much more importantly, quantity was the key.

Duck comics enthusiasts of the world can consider themselves lucky though, for not just was Carl Barks spectacularly industrious in the quarter century during which he worked for Disney—producing over 500 stories all in all—he also consistently maintained high standards in his writing and his draftsmanship. Barks would of course not be sending Donald on grand adventures in every story he wrote. In fact, most of his stories are ten pagers, and never feature the protagonists leaving Duckburg, and would be relatively close to earth, with plots usually centering around Donald trying his hands at new jobs, like milkman or lifeguard at a beach or frog breeder (Barks would later joke that he was aided in that he had spent most of his twenties and thirties working a long succession of odd jobs), or engaging in quarrels with his neighbour Jones, or Donald playing tricks on his nephews or them playing tricks on him, etc. The schedule would broadly speaking be that Barks would write a dozen or so ten pagers, write a longer adventure of between twenty-five to thirty pages, and then go back to another dozen or so ten pagers.

The world-building that we gradually see taking place in Carl Bark’s stories is the direct product of the paradigm in which he worked. It all happens organically, ad hoc in as far as any particular story that Barks is working on needs it. When his readers were informed in 1944 that Donald Duck and his nephews live in the city of Duckburg in the (fictional) state of Calisota, Barks did so simply because in the story he was writing at the time (the ten-pager High-wire Daredevils), he needed Donald Duck to have an address. The same was true for the characters that populate the ‘Ducks universe’, and indeed many characters would only appear in a single story, and then never to reappear again. Others would after their initial appearance continue to spark ideas in Barks’ mind, and so he would invite them back for further stories, until they eventually became Donald Duck regulars. Though Daisy Duck and the three nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie may have preceeded Barks’ entrance onto the stage of comics, many characters whom reader today identify as integral to the Duck universe were the creations of Barks, such as Donald’s insanely lucky cousin Gladstone Gander and the ingenious inventor Gyro Gearloose—the latter only ever having been created for the purpose of a single one-frame throwaway gag!

And Barks’ Ducks comics author contemporaries recognized Barks’ talent and inspiration behind his characters. And, since the intellectual property all ended up being Disney’s anyway, and they were thus allowed to use Barks’ characters for their own ends, in their own stories, so they did. Unfortunately, this would not benefit Barks’ financially, but it would benefit him artistically, in that as other writers and artists made use of his characters and settings, it meant that he would not have to reintroduce them every time he made use of them. They would remain there, fresh in his readers’ minds, allowing Barks to write other stories while his colleagues tended to them. And this entire discussion brings us to Barks’ indisputably greatest creation: Uncle Scrooge McDuck.

Early on, it became a bit of a running gag among Donald Duck writers that the titular American Pekin has an absurdly multi-branched and diverse family tree, filled with all kinds of distant cousins and uncles. It was more than just a gag, of course, it was a useful plot device, since it meant that if you wanted to write a Donald Duck story where Donald tries his hands at X, why, you could just invent a distant cousin of Donald who works in X, and there’s your set-up for the story established. To give some examples from Barks himself, there is Cousin Cuthbert Coot, who is a cattle rancher out west (and only ever appears in the story Webfooted Wrangler from 1945), and Cousin Whitewater Duck, who is a lumberjack (and only ever appears in the story Log Jockey from 1962). In 1947, Carl Barks needed a grumpy, rich uncle for a Christmas story he had in mind, and so he invented Scrooge McDuck. Scrooge, because obviously, and McDuck because, well, we all know the stereotype about the greedy, cheap, stingy Scotsman, now don’t we?

Already on the first page of the story, Christmas on Bear Mountain, we are introduced to Scrooge McDuck. Like his namesake, he is a bitter old miser, right down to a penchant for using the phrase “Bah, humbug!” Spending the season alone in his massive mansion, he hates Christmas as indeed he seems to hate pretty much everything. “Everybody hates me, and I hate everybody!” he declares. But this is no mere retelling of A Christmas Carol with anthropomorphic ducks standing in for Victorian Londoners. The plots scarcely resemble one another. Scrooge is envious of all the people who seems to have fun giving presents to one another—“I’ve never had any fun!”—so he decides to give his nephew Donald a gift this year around. But first, if Donald will have to pass a “little test” of Scrooge’s devising…

That very afternoon, a telegram arrives at Donald’s residence, inviting him and his nephws Huey, Dewey, and Louie up to Scrooge’s cabin in the mountain to spend the holidays. This greatly enthuses all four of them, seeing it has earlier been established that Donald is broke and so can afford his nephews neither gifts nor a great Christmas dinner this year. They travel up there and they settle in.

So what is Scrooge’s test? Well, for some reason, Scrooge has gotten it into his mind that the younger generations of the day are cowards, and so he will only reward Donald and the nephews if they can prove themselves to be brave. He therefore plans to dress up as a bear, go up to the cabin on Christmas night, and do his best scare the living daylights out of them. If they are undeterred, then they deserve his gifts, having proven themselves not to be cowards.

On Christmas Night however, Donald and the nephews cuts down a tree to decorate, and wouldn’t you know, in the tree is a sleeping bear cub hiding, whom they bring into the cabin unknowingly. The bear cub wakes up once they have finished decorating, and, well, hilarity ensues, in particular because it turns out that Donald is of course deathly afraid of bears. Eventually, the cub’s mother comes to the cabin, looking for her missing son. She doesn’t find him right away though, but she finds the fully stocked fridge, and proceeds to gorge on its contents. Having had a feast, she goes to sleep before the open fire, where Donald and the nephews find her. Donald is entrusted with tying her up while the nephews continues their mission of trying to capture the bear cub. Unfortunately, before Donald can finish his task, the bear yawns in her sleep, causing Donald to faint and fall right in her arms. Apparently, she is so deep asleep that she doesn’t notice it.

And, so, later, when Uncle Scrooge turns up in his bear custome, that’s where he finds Donald. Scrooge comically misinterprets the situation, thinking that Donald has tamed the beast and has now laid down to sleep right next to it, totally unafraid of it, and thus insanely brave. Deeply impressed, Scrooge concludes that he has severely misjudged his nephew, runs back to his car and tells his butler to immediately get the mansion in order and to prepare the feast of his nephews’ lives—“Nothing is too good for such ducks!”—and come Christmas Day, that is indeed what Uncle Scrooge treats them to. And a very merry Christmas to y’all!

It is generally agreed among Barks’ fans that Christmas on Bear Mountain is not one of his strongest stories. It is quite frankly rather phoned-in, contrived, slapsticky, and forgettable, and had this been Uncle Scrooge’s only appearance, the impression he would have left would have been so weak that it is unlikely people would have remembered him any more than they remember the aforementioned Cousin Cuthbert or Cousin Whitewater.

Barks himself would admit as much, when later asked if the character had received favourable comments after his initial appearance, responding “Not a word!” But, he would also say, already while he was writing the story, he was beginning to feel that the character of Uncle Scrooge had potential, and that as he was putting the finishing touches to his drawings, he was feeling rather that he was doing poor old Scrooge a disservice portraying him as he did. That there were adventures for him to go on! And, of course, when you think about it, it only makes sense. Donald’s relatives had been invented to serve as a plot devices for him to engage in further stories, and since we all like to imagine that rich people live very interesting lives and go on adventures all the time, why, it only made sense to give Donald Duck a wealthy uncle.

Still, the next story to feature Uncle Scrooge, The Old Castle’s Secret (published less than six months after Christmas on Bear Mountain), focused not as much on Uncle Scrooge being wealthy as much as on him being Scottish—after all, there was that Mc in McDuck. This time we meet a far merrier Scrooge than the one seen in his first appearance, and though he is still an old timer of course, he no longer stoopingly leans on a cane for support, instead being active and full of energy. This Scrooge calls his nephews over to recruit them on a quest of his, they are to go to the ancestral castle of the great and mighty Clan McDuck in the Scottish Highlands—an imposing medieval fortress—to find the treasure of Sir Quackly McDuck which has been lost for centuries and is believed to be located somewhere on the property. The adventure is considered a classic, and showcases Barks at his very best, the plot drawing on horror, mystery, and science fiction, and it features a rather satisfying twist ending.

By the end of the story, there could be no doubt about it in the readers’ minds: Uncle Scrooge was a character that was here to stay...

Comments