Alternate Crimes: The Community

- Sep 12, 2019

- 10 min read

By Wm Garrett Cothran

“You know, I hadn't realized before how much non-crime fiction just sort of ignores the fact that crime is a thing that happens.”

The above is what brings us to the new topic at hand. While still focused on the idea of crime as it relates to alternate history, it is now time to look at crimes which have an impact upon a community.

Not merely a particular neighborhood in a particular city, but that more fluid notion of a community. How a crime effects the zeitgeist of a society.

A single criminal act which can have very little physical impact upon a community can have long lasting effects. Effects which last well beyond the crime itself, the victims, or the people who perpetrated it. Yet in considering the impact a crime can have on a community as a whole, you will find a treasure trove of material for any number of “What If” scenarios and settings. Or you can make use of crime as a backdrop to your overall story.

As a back drop nothing works better than a serial killer: a strange phantom lurking in the shadows ready to prey upon innocent victims, while good hard-working people try to live their lives. Or it can be the much more common event of a unknown killer who preys on a particular community and, in effect, brings out all the racism, xenophobia, hatred, and distrust that community has for outsiders - or even itself.

In either case, the focus here will be on four crimes and the effect these crimes had on the communities in which they occurred.

The four will be: Jack the Ripper, Joseph Vacher, Kitty Genovese, and Satanic Cults in Kern County, Ca.

A brief overview of the crimes will be made, but the focus is not on the well documented acts, but more how people and a society reacted to said crimes. These reactions are important from an alternate history or a general writing perspective, because they help to illustrate how a crime can shape the community in which it occurs.

To many, he is the first real serial killer in modern history. To others, he is that perfect image of a killer. A lonely, and fog covered, London street. A prostitute, always a pretty one, walking alone. Suddenly a man approaches. He is wearing fine shoes, a cloak, and a top hat. Some will have the man with a cane and speaking ever so sweetly to the woman. Others have him producing a sharp blade as he sneaks up on his victim.

Jack the Ripper was a killer who was never caught but who still influences art and literature to this very day. If one wishes to learn about him, there is more then enough research on him, his crimes, and who he may or may not have been.

The focus here is: how did London react to this crime?

Well, with Whitechapel in 1888, it is important to understand that the region was an area of extreme to moderate poverty with people living in unsanitary slums.

What exactly is a slum? Well according to the London Daily News in 1881:

“ Here is a street in St George’s-in-the-East.

It contains about seventy, four-roomed houses, and the inhabitants average four to every room...”

The article explained poor wages, crowding, rats, and heart-breaking tales.

By 1888 nothing really had changed. Yet when a serial killer brutally murdered five prostitutes, the London Daily News quickly focused not just on murder, but “the moral and social degeneration” of the area. Many newspapers of the period spoke of Jack the Ripper - honestly how could one not? – but around this sensationalist news was a big reaction to just how bad were the slums of Whitechapel. The reaction was so strong that by 1900, nearly the entire area was demolished and improved.

The UK has had similar anti-slum movements - all linked to notions of hygiene, and fighting crime. Yet this theme continues to come up in articles, speeches, and simple conversations about the victims of Jack the Ripper: Not how they should not have died, but a refrain most familiar to modern ears of “if they were not so poor or immoral, they would not be victims.”

Many stories focus on Jack the Ripper but do so only as it pertains to the criminal investigation or the possible killer... when there is much to be said for how the gruesome killings brought to light another issue: the poverty within London.

This man was… well he was a killer of little shepherds in 1890s France. He is often overlooked, but he holds a very important position in criminal justice for many, as Vacher, prior to his murders, actually went to an insane asylum.

Yes, he was by all accounts insane... and then declared cured.

His defense attorney at trial said, “if he killed a man hours after leaving the Asylum would we hold him guilty? Now ask if the months after leaving remove that feeling this man is innocent.”

We have all heard of people claiming insanity, but the trial of Vacher also had a man named Alexandre Lacassagne - one of the pillars of criminology even to modern day.

Lacassagne in the trial presented a new view to insanity which was “if he is so crazy, why did he take every action needed to not be caught?”

For example, Vacher was a traveling vagrant but he always had enough money to ensure he would not be arrested for vagrancy. Vacher would commit murders only when alone, and afterwards he would walk dozens of miles away as fast as he could. Vacher would grow a heavy beard and not cut his hair until after the murder at which time his appearance would change greatly. Lacassagne would be right at home on the TV show Mindhunter or even CSI, with his focus on evidence showing the actions of the criminal, and also showing the criminal's state of mind.

Lacassagne was around in a time when people were seeing insanity in a new light. Namely, that some people may just be victims of society, and deserving warmth and compassion instead of punishment and scorn. Alongside this, was a growing movement of people insisting that some people were just bad by nature. Lacassagne was an aberration to these debates in bypassing it all with the quote “Every society gets the kind of criminal it deserves.”

That should ,to anyone interested in Alternate History, be the main focus of any talk about crime and society.

Lacassagne, and, in effect, Josef Vacher created in France a debate which spread to the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, the United States - even Japanese and Austo-Hungarian psychologists spoke about the case. As a case, many tended to ignore it, even though Vacher killed somewhere between eleven people and twenty-seven people to Jack the Ripper’s five.

Vacher, though, had this impact on psychology, criminology, and even French criminal law, because this case was one of the first times that science of the mind was mixed with forensics, to show not that Vacher was a crazed "foaming-at-the-mouth" killer, but a calculated murderer. Over time this stopped being new and became commonplace, but this is where it started. Once more, the key is on how the murderer impacted society.

Kitty Genovese is someone about whom you may not know, but anyone who has taken a psychology or sociology class has certainly learned about her.

One night in New York a woman was murdered on the street. She was murdered and screaming for help yet her dozens if not hundreds of neighbors just watched. They did nothing. This is called the Bystander Effect. It is what makes people know that in a group no one will act.

It was what made Alan Moore’s Rorschach decide to put on a mask and fight crime.

Are you outraged? Well, you should know that all of that is rubbish. 100% rubbish. Made up by a mixture of rumor, misleading and misreading of newspapers, and police being rather silent on the matter.

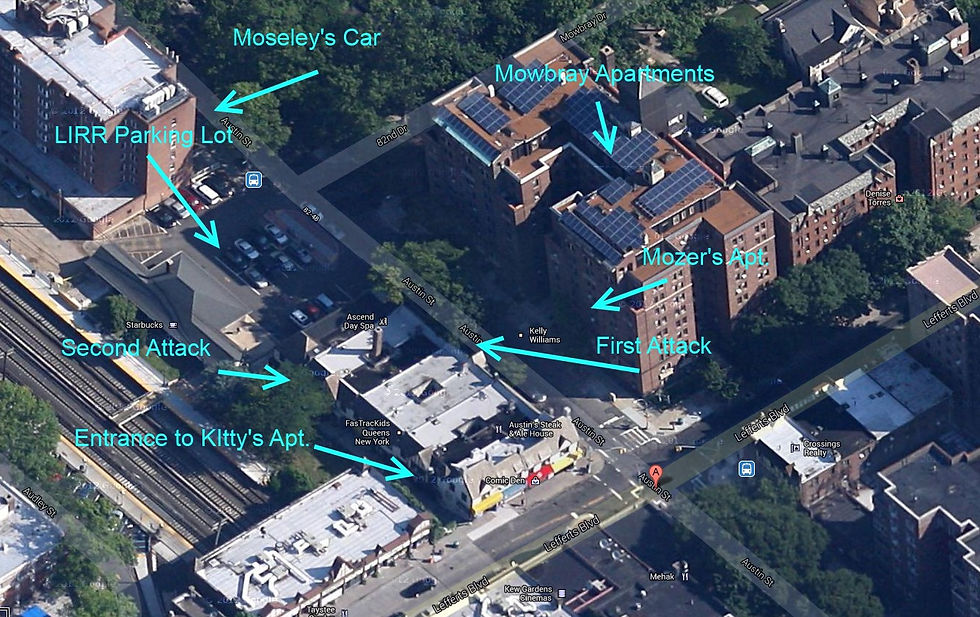

The murder itself was done by a man called Winston Moseley. Moseley was a married man who worked on computers in the 1960s. He also broke into homes, killed people, and may have been a serial killer. Yet somehow the view people got of the crime was about bystanders doing nothing. Look at the picture below and you can somewhat understand why the by standing notions are not so cut and dry.

Genovese was attacked on Austin Street in New York. It was here she called for help and people witnessed it. Yet while some called the police, most did not even make it to their windows in time to see anything but a lone woman on the sidewalk or, in many cases, nothing at all.

The second attack was out of the view of most, and inside of an apartment hallway. So, the crime was not so much bystanders doing nothing but simply a sadly all-too-common murder? So, why did the community view the crime in such a strange way?

First and foremost, Kitty Genovese was a lesbian living with her girlfriend. And this is 1960s New York, and being a homosexual is not legal. It gets you arrested, it gets you fined, the Stonewall Riots (a landmark event in US LGBTQ history) did not occur until 1969. In 1964, though, a "nice girl" like Kitty was “treated with respect” and her relationship was kept secret.

Secondly, the police, in seeking witnesses and more, spoke to many neighbors, and the reporters of the case created a narrative which played up one or two witnesses saying “I did not want to get involved” mixed in with the fact that police interviewed thirty-eight people. So the papers ran with “Thirty-Eight Watched While Woman Slain.”

This, of course, was a very big deal, and not just in New York, but in the USA as a whole. It cemented the popular idea in 1964 that society was getting more and more apathetic. That crime was rampant, and police could do little to save you, and even your own neighbors would not lift a hand to help you.

That mentality gave rise to politicians which gained political office by being “tough on crime”, and it likewise helped usher in the first real spike in personal firearm ownership. Some have even made a line between Kitty Genovese being murdered and Neal Knox (NRA president in the 1980s and famous/infamous for reforming the NRA into a staunch 2nd amendment political lobbying group) stressing that the “only way to stop your family from being murdered in some New York street while the neighbors watch is a gun in your belt.”

The final thing we will discuss today is not so much about the crime, but about the interesting notion of innocent people being punished.

Kern County, California, has a long history as a farming community which happens to hold a city containing well over 200,000 people in it. It is a small town which just so happens to be a big city.

In the USA in the 1980s there was a panic in various communities about Satanic ritual abuse. It seemed as if, all over America, as Ronald Reagan was single-handedly defeating Communism, people were worshiping the Devil and abusing children.

This in turn lead to the Day-Care Abuse scandals in which people accused day cares of abusing children. In Kern County, all of this hysteria turned into thirty-six people being convicted of being part of a “Satanic-paedophile-sex-ring” where as many as sixty children claimed to have been abused.

What is important to note is that police questioned children, unsupervised, for upwards of six hours at a time, and all investigators admitted to operating on the principle that “we know what happened to these kids - we just need them to say it out loud.”

Thirty four of the convictions were overturned on appeal with the last two having died in prison (and as such, had no grounds for appeal).

This seems like the most unpleasant of topics as it involves children - but as this was a mass hysteria, it seems less stinging. Yet the focus should be on the hysteria itself: It was an organic event which had little-to-no basis in reality, but was deemed of such importance that not only did police and public officials strive to fight it, the people in various communities demanded that more be done.

The cases led to the creation of rules and standards for interviewing children and made law enforcement aware of principle that “the accusation alone may harm this person,” and eventually led to treating such cases like walking on eggshells. In the era of #MeToo, such an attitude by law enforcement is looked down upon, but said viewpoint has its roots in a period in US history when the hysteria overtook common sense, leaving behind lingering fears of future lawsuits and wrongful convictions.

What does all of this mean for Alternate History? What does it matter that Jack the Ripper influenced a discussion on poverty, or that a lone woman killed on a street affected views on self defense, or even how people were falsely accused?

It goes to show that the smallest of actions can have massive effects on a society. That there should be a real focus should be on how alternate crimes (or the absence of crimes that occurred in OTL) could and would influence communities and the way that communities takes shape. Such crimes are part of that background of events that consumes the minds of people in the moment, and is only debated and rationalized into some kind of logic afterwards.

As with the quote at the very top of this article crimes are important to look at even when crime is not the main focus of a story. An author can show so much detail and so much background just by how people react to crime. He or she can show a community suffering fear from a murderer lurking about their neighborhood and what long-range effects this can bring about, or can use it to show those who finally see the conditions of other parts of a society only brought to light by violent acts. There is the sheer overwhelming relief one experiences when “the monster has been caught”... only to be followed up by knowledge “the wrong man was convicted.”

Crime has a certain allure to it. It is somehow both exciting and scary. It is something inherent to one extent or another within all societies, all people, all cultures. It is a universal thing for a community to have to deal with crime. By bearing this in mind when crafting Alternate History, one finds oneself looking at events in different ways. Not merely that Person A has been spared from a gruesome death in OTL and is now alive and free to make a cure for cancer, but also that because Person A never died, the news never pointed out what a slum Person A lived in. How in this slum, there was a school so run down that students were getting cancer from asbestos, and the light of media attention now focused on it led to a series of general reforms to improve the area.

It may not seem as exciting to some but when you think of Alternate History you are thinking, in effect, of a stone landing in a pond. The ripples are what matter. Crime is, and always will be, a stone. So crime and alternate history always should go hand in hand - even when the focus is on something other then crime.

Wm. Garrett Cothran is the author of How Tall Is The Grass In Germany? published by Sea Lion Press

Comments